Automobile Magazine

September 1993

Vintage Stuff

Edited by Mark H. Schirmer

Formula 1: The Seniors' Division

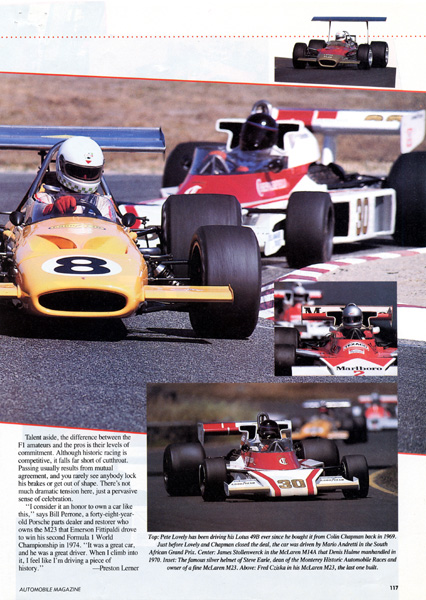

For an exhilarating and ghoulish moment, it was possible to imagine that this was the inaugural U.S. Grand Prix West in 1976. Ronnie Peterson's March 761 was leading Tom Pryce's Shadow DN5 down Shoreline Drive, their cars darting over the undulating pavement, their Cosworth-Ford DFV engines barking as they geared down for Turn One. But, no, this wasn't the Long Beach of old. It was Laguna Seca last summer. Peterson and Pryce had long since departed the Grand Prix scene -- both, ironically, killed in freakish racing accidents -- and the Formula 1 seats they once occupied were now filled by thirty-six-year-old specialty coffee importer Mark Mountanos and forty-eight-year-old rare stamp dealer Warren Sankey. Behind them streamed a gaggle of other obsolete Cosworth-era Grand Prix cars -- Brabhams, Lotuses, McLarens, Williamses, not one but two V-12 BRMs, and a glorious Ferrari 312 once driven by Chris Amon--all in their original colors and markings.Here at the Monterey Historic Automobile Races, of course, spectators are accustomed to the sight of vintage racing machines in full regalia. But the emerging popularity of F1 cars built between 1966 and 1983 -- the largely non-turbo, 3.0-liter years -- represents a new and exciting trend in historic racing. "When I bought my March," Mountanos says, "Formula 1 cars were selling for not much more than mid-Sixties sports-racing cars. It just didn't make sense. Why would you buy a Volkswagen when you could get a Ferrari?"As recently as ten years ago, there was so little interest in last year's F1 cars that you could hardly give them away. Now, thanks to buyers like Mountanos, there are about fifty raceable Grand Prix cars in the United States. Most of their owners have banded together as an association dubbed Project One. "There's nothing formal about it," says historic racing paladin Steve Earle, who races a McLaren M23 when he's not running the Monterey historics. "It's like a flying club. We're the Confederate Air Force of racing cars."The spiritual father of the historic F1 movement is Pete Lovely, who bought a Lotus 49B directly from Colin Chapman and campaigned it as a Grand Prix privateer in 1969. Lovely later restored the car to Team Lotus's Gold Leaf livery and started running it, along with an old Williams, at vintage-car meets. Sankey, a longtime F1 devotee, was so energized by the spectacle that he bought a McLaren M26 for himself. "Then Fred Cziska came up to me and asked, 'Where can I get one of those?'" Sankey recalls. "And it kind of snowballed from there." Well, sort of. In the early years, most traditional vintage-racing drivers wanted nothing to do with 3.0-liter F1 cars. What was the point, the thinking went, of racing cars that had been winning Grands Prix only a few years earlier? |

"I remember thinking that they were nuts, and I asked them, 'Why are you guys doing that?'" says Dick James, who raced motorcycles and hydroplanes before buying a McLaren M14A. "The next race, Stoney [James Stollenwerck] said, 'Put on your helmet,' and I got into his car. And then I knew why they were doing it. Like Stoney said, 'The first needle is free.'" Although the number of Grand Prix junkies crept ever upward, they were treated like second-class citizens until Earle bought his M23 and more or less legitimized the movement. As more people followed Earle's lead, prices began to climb from as little as $40,000 or $50,000 back in the mid-Eighties to $300,000 to $500,000 before the collector craze fizzled at the end of the decade. Today, it's possible to get into a decent car for $150,000, although chassis with significant race histories and Ferraris of any sort can command twice as much. Understandably, owners aren't eager to stuff such valuable investments -- or themselves -- into any concrete barriers. As Mountanos puts it: "I'm not one to take any chances. I have nothing to gain. Winning is not all that important." Even while outdistancing the field at Laguna Seca, Mountanos says he wasn't driving harder than eight-tenths. Of course, eight-tenths is plenty fast in an 1100-pound car with 505 bhp. "Anybody with some experience can get around a track quickly in one of these cars," says Tom Claridge, 51, a new-car dealer who owns a Shadow DN8 -- the last American car to win an F1 race. "But really exploring the limits is pretty frightening. The acceleration is so fierce and the brakes are so incredible and you carry so much speed through the corners. It doesn't take you long to realize that if you make a mistake, there are going to be some pretty dire consequences." Talent aside, the difference between the F1 amateurs and the pros is their levels of commitment. Although historic racing is competitive, it falls far short of cutthroat. Passing usually results from mutual agreement, and you rarely see anybody lock his brakes or get out of shape. There's not much dramatic tension here, just a pervasive sense of celebration. "I consider it an honor to own a car like this," says Bill Perrone, a forty-eight-year-old Porsche parts dealer and restorer who owns the M23 that Emerson Fittipaldi drove to win his second Formula 1 World Championship in 1974. "It was a great car, and he was a great driver. When I climb into it, I feel like I'm driving a piece of history." -- Preston Lerner |

CAPTIONS:

Below: Bill Perrone at the wheel of a famous McLaren. Before it fell into Perrone's hands, the number 5 M23 was driven by Emerson Fittipaldi during his 1974 World Championship season.

Top: Pete Lovely has been driving his Lotus 49B ever since he bought it from Colin Chapman back in 1969. Just before Lovely and Chapman closed the deal, the car was driven by Mario Andretti in the South African Grand Prix.

Center: James Stollenwerck in the McLaren M14A that Denis Hulme manhandled in 1970.

Inset: The famous silver helmet of Steve Earle, dean of the Monterey Historic Automobile Races and owner of a fine McLaren M23.

Above: Fred Cziska in his McLaren M23, the last one built.

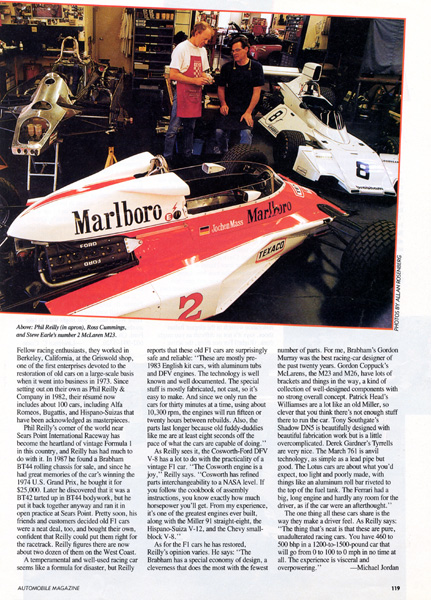

Phil Reilly & Company

It's one thing to drive an old Formula1 car, but it's quite another to keep it in one piece. Since racing -car manufacturers don't service what they sell, Phil Reilly & Company in Corte Madera, California, has become the unofficial factory repair center for obsolete factory machinery. Over the years, Reilly & Company has restored seven F1 cars and rebuilt more than twenty Cosworth-Ford DFV V-89 engines and a Ferrari 312 V-12. Altogether, it has had its hands on two dozen F1 cars, a unique perspective from which to comment on the relative merits of the most exotic racing cars on the planet. Of course, there's more to Phil Reilly & Company than old racing cars. It's the collaborative enterprise of three friends: Phil Reilly, master machinist Ross Cummings, and mechanic/philosopher Ivan Zaremba. Fellow racing enthusiasts, they worked in Berkeley, California, at the Griswold shop, one of the first enterprises devoted to the restoration of old cars on a large-scale basis when it went into business in 1973. Since setting out on their own as Phil Reilly & Company in 1982, their resume now includes about 100 cars, including Alfa Romeos, Bugattis, and Hispano-Suizas that have been acknowledged as masterpieces. Phil Reilly's corner of the world near Sears Point International Raceway has become the heartland of vintage Formula 1 in this country, and Reilly has had much to do with it. In 1987 he found a Brabham BR44 rolling chassis for sale, and since he had great memories of the car's winning the 1974 U.S. Grand Prix, he bought it for $25,000. Later he discovered that it was a BR42 tarted up in BR44 bodywork, but he put it back together anyway and ran it in open practice at Sears Point. Pretty soon, his friends and customers decided old F1 cars were a neat deal, too, and bought their own, confident that Reilly could put them right for the racetrack. Reilly figures there are now about two dozen of them on the West Coast. A temperamental and well-used racing car seems like a formula for disaster, but Reilly reports that these old F1 cars are surprisingly safe and reliable: "These are mostly pre-1983 English kit cars, with aluminum tubs and DFV engines. |

The technology is well known and well documented. The special stuff is mostly fabricated, not cast, so it's easy to make. And since we only run the cars for thirty minutes at a time, using about 10,3000 rpm, the engines will run fifteen or twenty hours between rebuilds. also, the pars last longer because old fuddy-duddies like me are at least eight seconds off the pace of what the cars are capable of doing."As Reilly sees it, the Cosworth-Ford DFV V-8 has a lot to do with the practicality of a vintage F1 car. "The Cosworth engine is a joy," Reilly says. "Cosworth has refined parts interchangeability to a NASA level. If you follow the cookbook of assembly instructions, you know exactly how much horsepower you'll get. From my experience, it's one of the greatest engines ever built, along with the Miller 91 straight-eight, the Hispano-Suiza V-12, and the Chevy small-block V-8." As for the F1 cars he has restored, Reilly's opinion varies. He says: "The Brabham has a special economy of design, a cleverness that does the most with the fewest number of parts. For me, Brabham's Gordon Murray was the best racing-car designer of the past twenty years. Gordon Coppuck's McLarens, the M23 and M26 , have lots of brackets and things in the way, a kind of collection of well-designed components with no strong overall concept. Patrick Head's Williamses are a lot like an old Miller, so clever that you think there's not enough stuff there to run the car. Tony Southgate's Shadow DN5 is beautifully designed with beautiful fabrication work but is a little overcomplicated. Derek Gardner's Tyrrells are very nice. The March 761 is anvil technology, as simple as a lead pipe but good. The Lotus cars are about what you'd expect, too light and poorly made, with things like an aluminum roll bar riveted to the top of the fuel tank. The Ferrari had a big, long engine and hardly any room for the driver, as if the car were an afterthought." The one thing all these cars share is the way they make a driver feel. As Reilly says: "The thing that's neat is that these are pure, unadulterated racing cars. You have 460 to 500 bhp in a 1200-to-1500-pound car that will go from 0 to 100 to 0 mph in no time at all. The experience is visceral and overpowering." -- Michael Jordan |

CAPTIONS:

Corte Madera, California is home to Phil Reilly's house of wonder. As the photos on this page (right and below) show, Reilly and his gang service more than just Formula 1 cars. Exotic toys of all shapes and sizes are more than welcome.

Right: In addition to his repair and service expertise, Phil Reilly drives vintage Formula 1 cars, too. He bought this 1974 Brabham BT44 for $25,000 in 1987, fixed it up, and took it on the vintage-racing circuit.

Above: Phil Reilly (in apron), Ross Cummings, and Steve Earle's number 2 McLaren M23.