Thrill of the Hunt

For more than a decade, the battle for supremacy in America's premier racing class was fought with Indianapolis roadsters.

This is the story of one such race car.

Story and Photography by D. Randy Riggs

From 1953 through 1963, the Indianapolis 500 saw its 11-row 33-car grids filled with colorful, fast and formidable Offenhauser-powered Indy roadsters. Shaped like a Cuban cigar on wheels, today they're known as dinosaurs, but on a paved oval tracks from the 1950s through the early '60s, roadsters were as good as it got -- state-of-the-art -- and then some. Not that there were many paved oval tracks in those days. Only Milwaukee, Trenton and Indianapolis lacked the dirt and dust that was the DNA of American racing (Daytona's experiment with roadsters ended in disaster in 1959). But the big 2.5-mile oval at 16th and Georgetown was the raison d'etre for these high speed weapons.

Indianapolis was the race -- the one that mattered more than all the others rolled into one. And there were plenty of others -- gritty, rut-filled ovals and horse tracks that criss-crossed the country where a driver with enough determination, talent and bravado could earn a living wage if his luck held on the Championship Trail -- the American Automobilie Association's National Championship circuit or after 1956, the United States Auto Club, better known as USAC. Truly gifted and fearless wheelmen could go on to fame and fortune -- but the potential for violent death hounded them through every turn.

Yet virtually every last one of the he-men in this cadre of drivers dreamed of the big one -- putting their mug on the Borg-Warner Trophy and taking that big swig of milk after winning the Indianapolis 500 and letting it run off their chin. For them the risks were worth it.

But first they had to make the show.

ROADSTERS ARRIVE

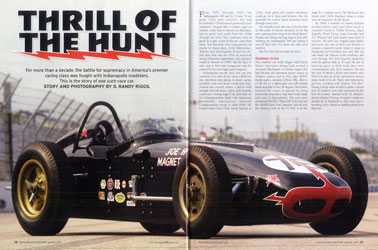

The roadster era really began with Frank Kurtis' innovative design built around a standardOffenhauser 4-cylinder engine that had become the dominant power source in midgets, sprints and at Indy after WWII. Kurtis took a standard 270cid Offy, offset it to the left in a lightweight and stiff tubular frame and laid it over 36 degrees. He further lowered the center of gravity by usiing tension bar suspension that had a wide range and ease of adjustablity. The cars were christened KK500s. When Bill Vukovich put the KK500 Keck Fuel Injection Special into the winner's circle at the '54 500, it set the stage for a roadster era at The Brickyard that lasted until 1964. Roadster ideas to come were all variations on this theme.

By 1960, a number of chassis builders besides Kurtis had tried their hand at roadster trickery. Eddie Kuzma, Quin Epperly, Floyd Tevis, Jujie Lesovsky and A.J. Watson had each tasted some level of success. All were Los Angeles-area based, and every last one of them was known to possess a master's touch when it came to designing and building race cars. But the tide swept the Watson to the forefront, and even though the wild Epperly laydowns tood the grid at Indy in '57 and '58, the 33 starting spots at Indy each May were overpopulated with A.J.'s roadsters. He and his crew of nearly a dozen parat-timers, who filtered in and out of the operation at various times, built 23 in all. There were fabricators, go-fers, welders, and Wayne "Fat Boy" Ewing, a body man second to none -- whose love of roadsters was only surpassed by his love of women. Married with 12 children, metal-shaper Ewing thought roadsters should be as beautiful as they were fast -- sweating every detail in making them look that way.

Ewing's opportunity for building an entire race car came during the summer of 1959. Boss A.J. would hang around the Watson digs at 421 W. Palmer in Glendale during the winter months, but headed for Indianapolis at the first spring thaw. And in 1959, there were a couple of orders for cars that Watson told Ewing to handle. "Here are the blueprints. I'm going to Indy."

It was a golden opportunity. Dean Van Lines wanted one along with Joe Hunt, of Joe Hunt Magneto fame. it would be the only new race car Hunt would ever own -- not inexpensive because Watson roadsters sold for about $13,000 less than the ubiquitous $10,000 Offy.

With Ronnie Ward's help (Ronnie was the brother of Indy Champion Rodger Ward) Ewing turned out two beauties that everyone called Watson copies -- which they were -- but Ewing's creations had a longer nose and flat sides. And, in the irony of ironies, tin-man Ewing built the cars with a fiberglass nose and tail -- go figure. Ewing's eye for coachwork was showcased in these two cars, and they looked like they were going 150mph sitting still.

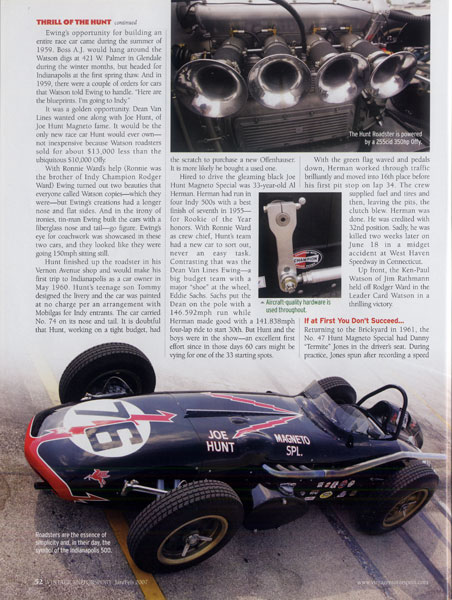

Hunt finished up the roadster in his Vernon Avenue shop and would make his first trip to Indianapolis as a car owner in May 1960. Hunt's teenage son Tommy designed the livery and the car was painted at no charge per an arrangement with Mobilgas for Indy entrants. The car carried No. 74 on its nose and tail. It is doubtful that Hunt, working on a tight budget, had the scratch to purchase a new Offenhauser. It is more likely that he bought a used one.

Hired to drive th egleaming black Joe Hunt Magneto Special was 33-year-old Al Herman. Herman had run in four Indy 500s with a best finish of seventh in 1955 -- for Rookie of the Year honors. With Ronnie Ward as crew chief, Hunt's team had a new car to sort out, never an easy task. Contrasting that was the Dean Van Lines Ewiing -- a big budget team with a major "shoe" at the wheel, Eddie Sachs. Sachs put the Dean on the pole with a 146.592mph run while Herman made good with a 141.838mph four-lap ride to start 30th. But Hunt and the boys were in the show -- an excellent first effort since in those days 60 cars might be vying for one of the 33 starting spots.

With the green flag waved and pedals down, Herman worked through traffic brilliantly and moved into 16th place before his first pit stop on lap 34. The crew supplied fuel and tires and then, leaving the pits, the clutch blew. Herman was done. He was credited with 32nd position. Sadly, he was killed two weeks later on June 18 in a midget accident at West Haven Speedway in Connecticut.

Up front, the Ken-Paul Watson of jim Rathmann held off Rodget Ward in the Leader Card Watson in a thrilling victory.

IF AT FIRST YOU DON'T SUCCEED...

Returning to the Brickyard in 1961, the No. 47 Hunt Magneto Special had Danny "Termite" Jones in the driver's seat. During pratice, Jones spun after recording a speed of 141.472mph, hitting the wall and damaging the car's tail.

Repairs were made and driver Don Freeland got the nod. Freeland recorded one of the fastest speeds of the month, but too much nitro in the tank made the engine go south before his qualifying run was completed.

Veteran Paul Russo also made a few laps in the car but details are sketchy as to whether he made a qualifying attempt. He may have simply been invited to render an opinion about the car's handling.

Meanwhile, Eddie Sachs, driving the Dean Van Lines Ewing roadster, qualified again on pole and went on to finish second to A.J. Foyt's Watson. But portending a change on the horizon for Indy roadsters was Jack Brabham's ninth-place finish in a rear-engined Cooper Climax.

ANOTHER DISAPPOINTMENT

IMCA sprint car driver Keith "Porky" Rachwitz was tapped for the Hunt seat for 1962's 46th running of the Indianapolis 500. A jouneyman driver, Rachwitz tried hard but ran too slow. He also failed to get Jim Kimberly's rear-engined Buick into the race. Chuck Arnold then climbed behind the wheel of the Hunt Special and spun harmlessly.

The story goes that Jim Hurtubise had crashed Norm Demler's car, and Demler's engine was then transferred into the Hunt roadster, perhaps as a way of finding more speed. Hurtubise then jumped in and got the car up to competitive speed but was flagged off and went to the back of the line. The clock ticked down. Thus for 1962, the Hunt Magneto Special was a DNQ.

Wynn's Friction Proofing came aboard as a major sponsor for 1963, and the car was festooned with an entirely new paint scheme and No. 25. But the team stuck with the old style tall Firestones while others like Parnelli Jones went with the new, wider tires Firestone had introduced thatyear, called "Flintstones." Al "Cotton" Farmer was scheduled to drive, but was injured racing a midget in Toronto April 26. He was unable to drive at Indy.

Jimmy Daywalt was tapped for the ride, but waved off his attempt. He couldn't get the car going quick enough to do the job. Chuck Rodee, a terrific midget-driver was next to give it a try. He, too, didn't complete his run and was flagged.

Joe Hunt haad to climb the same mountain all underfunded teams face. Without deep pockets, there arent' the resources available to do dyno testing, older parts have to be used and the very best personel can't be hired.

The situation was much the same for 1964, and lowering the qualifying odds for Hunt and his roadster, the Indy establishment was in turmoil over the wave of lightweight rear-engined cars that were no more than competitive. No less and 12 made the 500 that year.

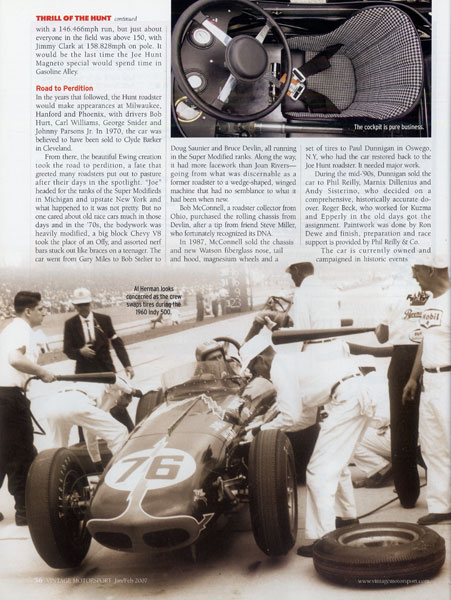

Before throwing in the towel, Chuck Rodee again gave his all in Hunt's No. 81. with a 146.466mph run, but just about everyone in the field was above 150, with Jimmy Clark at 158.828mph on pole. It would be the last time the Joe Hunt Magneto special would spend time in Gasoline Alley.

ROAD TO PERDITION

In the years that followed, the Hunt roadster would make appearances at Milwaukee, Hanford and Phoenix, with drivers Bob Hurt, arl Williams, George Snider and Johnny Parsons Jr. In 1970, the car was believed to have been sold to Clyde Barker in Cleveland.

From there, the beautiful Ewing creation took the road to perdition, a fate that greeted many roadsters put out to pasture after their days in the spotlight. "Joe" headed for th eranks of the Super Modifieds in Michigan and upstate New York and what happened to it was not pretty. But no one cared about old race cars much in those days and in the 70's, the bodywork was heavily modified, a big block Chevy V8 took the place of an Offy, and assorted nerf bars stuck out like braces on a teenager. The car went from Gary Miles to Bob Stelter to Dough Saunier and Bruce Devlin, all running in the Super Modified rands. Along the way, it had more facework than Joan Rivers -- going from what was discernable as a former roadster to a wedge-shaped, winged machine that had no semblance to what it had been when new.

Bob McConnell, a roadster collector from Ohio, purchased the rolling chassic from Devlin, after a tip from friend Steve Miller, who fortunately reognized its DNA.

In 1987, McConnell sold the chassis and new Wilson fiberglass nose, tail and hood, magnesium wheels and a set of tires to Paul Dunnigan in Oswego, N.Y., who had the car restored back to the Joe Hunt roadster. It needed major work.

During the mid-90s, Dunnigan sold the car to Phil Reilly, Marnix Dillenious and Andy Sisterino, who decided on a comprehensive, historically accurate do-over. Roger Beck, who worked for Kuzma and Epperly in hte old days got the assignment. Paintwork was done by Ron Dewe and finish, preparation and race support is provided by Phil Reilly & Co.

The car is currently owned and campaigned in historic events by DKD Enterprises, with James King and Duncan Dayton joining Dillenius as owners, who immediately christened the car, "Joe."

THE THRILL OF THE HUNT

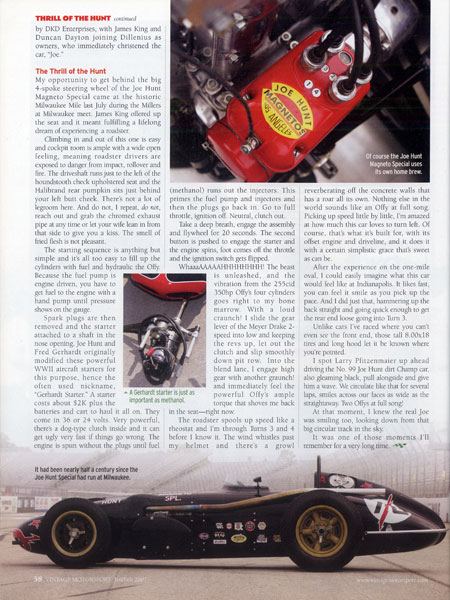

My opportunity to get behind the big 4-spoke steering wheel of the Joe Hunt Magneto Special came at the historic Milwaukee Mile last July during the Millers at Milwaukee meet. James King offered up the seat and it meant fulfilling a lifelong dream of experiencing a roadster.

Climbing in and out of thi sone is easy and cockpit room is ample with awide open feeling, meaning roadster drivers are exposed to danger from impact, rollover and fire. The driveshaft runs just to the left of the houndstooth check upholstered seat and the Halibrand rear pumpkin sits just behind your left butt cheek. There's not a lot of legroom here. And do not, I repeat, do not, reach out and grab the chromed exhaust pipe at any time or let your wife lean in from that side to give you a kiss. The smell of fried flesh is not pleasant.

The starting sequence is anything but simple and it's all to easy to fill up the cylinders with fuel and hydraulic the Offy. Because the fuel pump is engine driven, you have to get fuel to the engine with a hand pump until pressure shows on the gauge.

Spark plugs are then removed and the starter attached to a shaft in th nose opening. Joe Hunt and Fred Gerhardt originally modified these powerful WWII aircraft starters for this purpose, hence the often used nickname "Gerhardt Starter." A starter costs about $2K plus the batteries and cart to haul it all on. They come in 36 or 24 volts. Very powerful, there's a dog-type clutch inside and it can get ugly very fast if things go wrong. The engine is spun without the plugs until fuel (methanol) runs out the injectors. This primes the fuel pump and injectors and then the plugs go back in. Go to full throttle, ignition off. Neutral, clutch out.

Take a deep breath, engage the assembly and flywheel for 20 seconds. The second button is pushed to engage the starter and the engine spins, foot comes off the throttle and the ignition switch gets flipped.

WhaaaAAAAHHHHHHHHH! The beast is unleashed, and the vibration from the 255cid 350hp Offy's four cylinders goes right to my bone marrow. With a loud craungh! I slide the gear lever of the Meyer Drake 2-speed into low and keeping the revs up, let out the clutch and slip smoothly down pit row. Into the blend lane, I engage high gear with another graunch! and immediately feel the powerful Offy's ample torque that shoves me back in the seat -- right now.

The roadster spools upspeed like a rheostat and I'm through Turns 3 and 4 before I know it. The wind whistles past my helmet and there's a growl reverberating off the concrete walls that has a roar all its own. Nothing else in the world sounds like an Offy at full song. Picking up speed little by little, I'm amazed at how much this car loves to turn left. Oc course, that's what it's built for, with its offset engine and driveline, and it does it with a certain simplistic grace that's sweet as can be.

After the experience on the one mile oval, I could easily imagine what this car would feel like at Indianapolis. It likes fast, you can feel it smile as you pick upthe pace. And I did just that, hammering up the back straight and going quick enough to get the rear end loose going into Turn 3.

Unlike cars I've raced where you can't even see the front end, those tall8.00x18 tires and long hood let it be known where you're pointed.

I spot Larry Pfitzenmaier up ahead driving the No. 99 Jo Hunt dirt Champ car, also gleaming black, pull alongside and give him a wave. We circulate like that for several laps, smiles across our faces as wide as the straightaway. Two Offys at full song!

At that moment, I knew the real Joe was smiling, too, looking down from that big circular track in the sky.

It was one of those moments I'll remember for a very long time.