CAPTIONS:

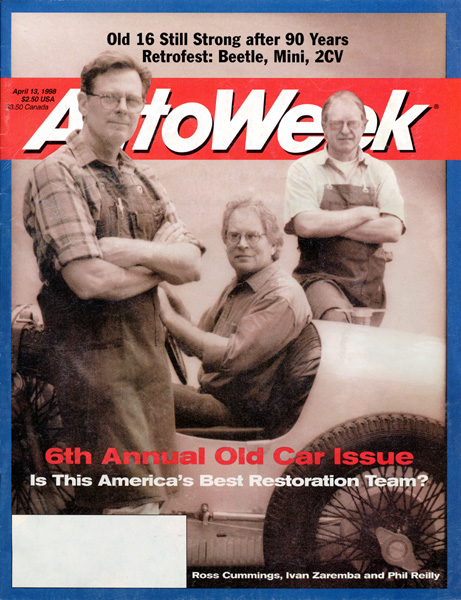

Phil Reilly (right) and partners Ross Cummings (far left) and Ivan Zaremba.

Says Ross Cummings, the introverted genius machinist who, according to Reilly, makes it all work, "We're all mechanics. That's our background. There's not a nickel's worth of business sense in this building."

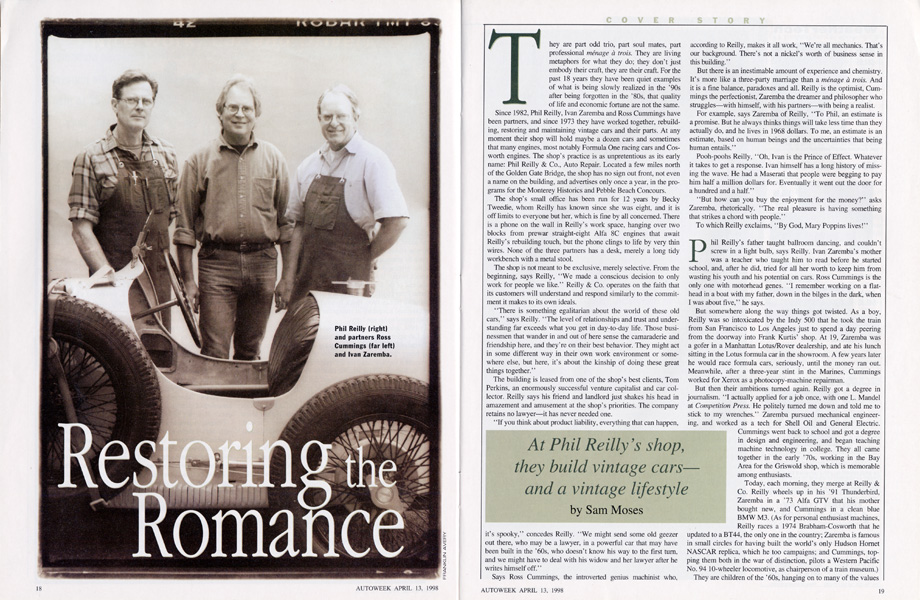

But there is an inestimable amount of experience and chemistry. It's more like a three-party marriage than a ménage à trois<. And it is a fine balance, paradoxes and all. Reilly is the optimist, Cummings the perfectionist, Zaremba the dreamer and philosopher who struggles -- with himself, with his partners -- with being a realist.

For example, says Zaremba of Reilly. "To Phil, an estimate is a promise. But he always thinks things will take less time than they actually do, and he lives in 1968 dollars. To me, an estimate is an estimate, based on human beings and the uncertainties that being human entails."

Pooh-poohs Reilly, "Oh, Ivan is the Prince of Effect. Whatever it takes to get a response. Ivan himself has a long history of missing the wave. He has a Maserati that people were begging to pay him half a million dollars for. Eventually it went out the door for a hundred and a half."

"But how can you buy the enjoyment for the money?" asks Zaremba, rhetorically. "The real pleasure is having something that strikes a chord with people."

To which Reilly exclaims, "By God, Mary Poppins lives!"

Phil Reilly's father taught ballroom dancing, and couldn't screw in a light bulb, says Reilly. Ivan Zaremba's mother was a teacher who taught him to read before he started school, and, after he did, tried for all her worth to keep him from wasting his potential on cars. Ross Cummings is the only one with motorhead genes. "I remember working on a flathead in a boat with my father, down in the bilges in the dark, when I was about five," he says.

But somewhere along the way things got twisted. As a boy, Reilly was so intoxicated by the Indy 500 that he took the train from San Francisco to Los Angeles just to spend a day peering from the doorway into Frank Kurtis' shop. At 19, Zaremba was a gofer in a Manhattan Lotus/Rover dealership, and ate his lunch sitting in the Lotus formula car in the showroom. A few years later he would race formula cars, seriously, until the money ran out. Meanwhile, after a three-year stint in the Marines, Cummings worked for Xerox as a photocopy-machine repairman.

But then their ambitions turned again. Reilly got a degree in journalism. "I actually applied for a job once, with one L. Mandel at Competition Press. He politely turned me down and told me to stick to my wrenches." Zaremba pursued mechanical engineering, and worked as a tech for Shell Oil and General Electric. Cummings went back to school and got a degree in design and engineering, and began teaching machine technology in college. They all came together in the early ;70s, working in the Bay Area for the Griswold shop, which is memorable among enthusiasts.

Today, each morning, they merge at Reilly & Co. Reilly wheels up in his '91 Thunderbird, Zaremba in a '73 Alfa GTV that his mother bought new, and Cummings in a clean blue BMW M3. (As for personal enthusiast machines, Reilly races a 1974 Brabham-Cosworth that he updated to a BT44, the only one in the country; Zaremba is famous in small circles for having built the world's only Hudson Hornet NASCAR replica, which he too campaigns; and Cummings, topping them both in the war of distinction, pilots a Western Pacific No. 94 10-wheelre locomotive, as chairperson of a train museum.)

CAPTIONS:

Reilly is the optimist, Cummings (above) the perfectionist, Zaremba the dreamer and philospher.>

They are children of the '60s, hanging on to many of the values of the 60's, having let go of the delusions and the tie-dye. Reilly holds up a photo of Judd Larson power-sliding his Champ Car at Williams Grove Speedway in the early '50s, his face smothered with powdery Pennsylvania clay. "This is what a race driver is supposed to look like," he says--although he sometimes works weekends on Ron Hemelgarn's IRL crew. "It's all the same shirt," he says, referring to his role in the modern racing world. Says Zaremba, "One of the things we all share is admiration of the engineers who conceived something, made it out of a chunk of metal, then jumped into the arena of competition to compare it against the others. These are our real heroes, and we see that passing away every day now. "But I love the way people react to these things," he adds, meaning the cars that he drives out of the shop. "It gives you faith that they recognize that all this stuff we are accumulating in mass quantities isn't a replacement for what came out of those days." At the shop, they walk a fine line between engineering a correct restoration, and between their own pursuit of perfection and the practical limits that must be applied if they are to make a profit--between "what the customer wants and what he's willing to pay for," says Reilly. They want things to work, but they don't want to corrupt the labor or ideas of their heroes. Says Chuck Mathewson, who came to Reilly from a Trans-Am racing team 14 years ago, "I've had to unlearn a lot of stuff. You look at a Ferrari part, and figure Guisseppe made this with a hammer on a tree stump, after a bottle of wine. I had to learn how to duplicate that look. For example, you can use a TUG welder instead of an oxyacetylene rig, as long as you know how to make it look a little ugly and crude it up a little bit." "Doing what we do here, you have to have a basic knowledge of the way the universe works," says Zaremba. "What makes this business different from from others is that there are no books. You have to try to figure out what the designer was thinking when he did something that may be problematic and baffling, and what's required now. It's wonderfully esoteric, and you have to be able to research. We like to look at the evolution of automotive design, and realize who stole from whom. Part of the reason we're successful is we enjoy those kinds of challenges.: Zaremba admits to being consumed by the lifestyle, but says, "I hate to think of myself as one-dimensional." After all, this is a published author of science-fiction stories, and a man who listens only to record albums. He pauses, and a small wry smile grows on the corners of his mouth. "Some of my best friends are not car people." Yes, but what does Zaremba actually do? "Overall, my job is to ensure that the finished product represents what the customer wanted," he says. "I spend a lot of time on the phone. For me, a gregarious person trapped in a nuts-and-bolts environment, that's a pleasure. But I'm also a little bit of a machinist, a little bit of a fabricator, I'm the guy that goes to the dyno and runs the engine on the test bed. I sort of operate as a foreman among our eight or 10 employees. And I drive all the cars," he adds, gesturing toward the ex-Alan Jones Williams F1 car in his space. Not a bad gig for someone who once wanted to be in that very seat. "But mostly," Zaremba says, "it's up to me to prioritize things." "Ivan is the Prince of Cacophony," says Reilly. "It comes with being Russian. He's the road tester and goes to lunch. That's what he does around here." Reilly also believes Zaremba is the best natural mechanic he has ever known. Reilly might poke fun of Zaremba for missing the wave of collector-car appreciation, but, in the late '80s when that wave was a tsunami, the shop chose not to ride along--even though it was in an ideal position to speculate and exploit the market, given its knowledge and connections, and might easily have made missions. Explains Reilly, "We made a decision not to get involved in the buying and selling of cars--the sordid part of our business. We always looked on buying and selling as a conflict of interest. That may be why we're still middle class, but it's also why we're still here." Says Cummings, "Phil is one of those guys who's nice to be around, because he's not into the what's-in-it-for-me part. We make decisions based on what seems like the correct thing to do. I think if you ask people out there, what you get from Phil Reilly is what he said you were going to get." But surely it must weigh on their minds, the wisdom of this choice they have made. Naturally, Zaremba is the one who rides such second thoughts into philosophical territory. "It comes up once in a while, these reappraisals of what we have done," he says. "And each of us has our own story about our choice to forego the lucrative fast track. I was a disaffected '60s radical, maybe, and I think that when I looked at the way the country was going, I kind of gave up my political idealism and retreated to my love of cars as a way of going down into this little backwater life. Three are certain regrets, now and then. I mean, I don't even own a house. I own a lot of cars. And there are people who think I'm an idiot for that--although I always say, 'Well, you can sleep in your car but you can't drive your house." But on the other hand," he continues, "I listen to wealthy businessmen--customers, clients, friends, whatever--who walk in here and point out how great it would be to work in this kind of an environment, as opposed to what they do. This job is a license to indulge in your romances, and nobody's stupid enough to overlook all of that. Sometimes I wish that I had done something different, but I don't know who I would trade lives with, either." The latter part of that sentiment is a feeling they all share. When a person can say that, he must be doing something right. |

|

|